THE ANSERBAK

“Halooo!” called the tenderfoot in the big woods, shouting for the joy of hearing his voice ring through the wooded dell.

“Halooo!” called back a faint voice. Once more the boy called, and once more his cry was repeated.

“Listen to the echo!” he exclaimed to the old guide who was with him. “It’s just as clear as anything.”

“Echo nothing!” snorted the old guide. “That just shows how much you know about it.”

“If it isn’t an echo, what is it?“ asked the bewildered boy, turning to stare at the guide.

“It’s the Anserbak, ” his guide replied solemnly. “I never saw one of them myself, but there’s plenty have. He always seems to be ahead of you just around the bend, and he mocks everything you say.”

“What does he look like?” asked the boy. “Oh, he’s something like a parrot, only bigger and lots gayer in his coloring. You just look out sharp and maybe you’ll see one while you’re up here.”

So the boy kept on calling and going in the direction from which the Anserback seemed to reply, but never a sight did he get of that sly mocker.

THE AXE-HANDLE HOUND

An autumn chill had crept into the air, and the brushwood bonfire, sending its little fingers of light into the unfriendly darkness, was the gathering place for the hunting party.

“Guess I’ll cut some wood and pile it up for the night,” suggested the lank guide, unfolding himself from his comfortable position in the fire-glow. He disappeared in the cavern of darkness.

In a few minutes he was back, “Doggone if I can find my axe,” he remarked. “Near’s I can remember I had it last night, down by that big oak—” He made another dash into the night, only to return empty-handed. “My own fault,” he muttered. “I reckon the axe-handle hound’s got it all right.”

“Axe-handle hound! Go on!” grinned one of the party.

“Mean to say you never heard of an axe-handle hound!” The guide cocked a solemn eye at him. “One of the worst nuisances in these here woods! It’s about one and a half times as big as an axe-handle and looks like its name, having a long body covered with rope-colored hair, and a hatchet face with saw teeth and cross eyes. The darn thing prowls around at night, looking for axe-handles, which is the only kind of food it’s been known to touch. Nicest axe I ever had,” bemoaned the guide, as he made another sally off into the night in search of the axe—or the hound.

THE BOAT HOUND

“Hey!” called Snowshoe Bill, the Big Woods guide, one morning. “The boat is gone. Did one of you fellows go fishing last night and forget to tie it up?”

The tenderfoot flushed. He was always doing something wrong. “I’m the one that had it last,” he confessed, “and I forgot to tie it up. What do you suppose has happened to it?”

“Well,” speculated the guide, “My private opinion is that the boat hound got it.”

“The boat hound! Never heard of suchathing!”

“Didn’t, huh? Well, he’s about the meanest customer I’ve ever run into. He sneaks along in the dark looking for boats that careless folks forget to tie and when he finds one, he swallows it right down. He has a great long body shaped like a boat, with big froglike feet, and four ears. With the front two he can hear everything in front of h’en, and with the back two he hears everything behind him. He has a big mouth like an alligator’s.”

“Where does this queer creature keep himself during the day?” the tenderfoot inquired with a little grin.

“He sleeps on the bottom of the lake in the daytime, but at night he’s wide wake, all right, looking for boats. Just you remember about him next time you take a boat out, young man.”

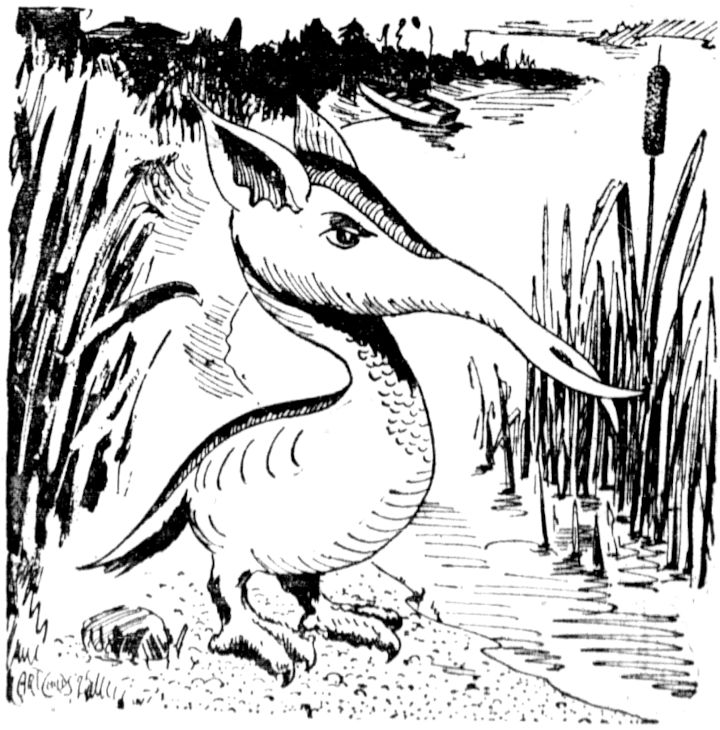

THE SIZZERBILL

Did you ever lose your hooks when you were fishing? Know how it feels to have a mighty tug on your line and think that it must be at least a whale who’s taken a fancy to your bait? Then you felt the line go limp, pulled it in, and found your hook gone. “A big fish must have got it,” you mourned.

Well, up in the North Woods the old fishermen assure you that it isn’t any fish that got your hook. Not at all: it’s the sizzerbill.

Now the sizzerbill is a mean customer. He’s always hanging around the weeds and rushes and in other places close to the shore. He’s mighty clever at keeping himself out of sight.

When he sees a fish struggling to free himself he will dart out under the water and—snip, snip—with his bill he cuts the line very neatly. And away goes the fish, free once more. And away goes the sizzerbill, off to another hiding place to make trouble for some other fisherman.

The sizzerbill is really half bird and half animal. He’s growing rarer and rarer, and it is only every year or so that some old guide up in northern Wisconsin or Minnesota reports that he caught a sight of one of these tricky fellows as he made for one of his favorite hiding places among the reeds.

THE SKEETEROO or STEEL-BILLED MOSQUITO

Kwasin, the old Indian, stalked into the camp to see his friend, the guide. The tenderfoot was introduced to the red-skinned visitor.

“By the way,” remarked the guide to the tenderfoot, “do you see those big scars on Kwasin’s arms and neck? That’s the work of the billed mosquito. Tell us about it, Kwasin.”

The Indian grunted, but remained silent.

“Long time since I’ve see any skeeteroos,” continued the old guide, “but years ago this country used to be full of ’em. They grew as big as chickens and had a bill ’bout six or eight inches long and as hard as steel. They kept ’em sharper ’n needles, with two little two-handed grindstones they had rigged up on the banks of the creek. Tell hint about the time a whole flock tackled you, Kwasin.”

“No, you tell um,” requested the Indian gravely.

“Well, one time when Kwasin was coming down Fish Creek in his canoe a flock of ’em come at him so he hurried to the banks of the stream, hauled his canoe out: turned it over, and got under it. The skeeteroos lit all over the canoe and pierced it full of holes with their sharp bills. Kwasin, to save himself, took a rock and clinched their bills underneath, until, all of a sudden, the skeeteros flew away with his canoe! Isn’t that so, Kwasin”

The Indian grunted solemnly.

THE SWAMP AUGER

The great woods of the North are criss-crossed with tracks, calling cards dropped by the animals for the keen eye of the tracker to read. On the edges of the swamps, where the ground sucks greedily at the feet of the hunter as though it would swallow him up for daring to intrude, these marks are often plainest.

To the tenderfoot the tracks are bewildering. The mark left by a skurrying rabit may suggest to his mind anything from a gliding silver fox to a majestic moose. The guides grin broadly as they watch a now-comer excitedly studying tracks.

“What is that?” asked the tenderfoot horsely, pointing to a webbed outline in the swampy ground.

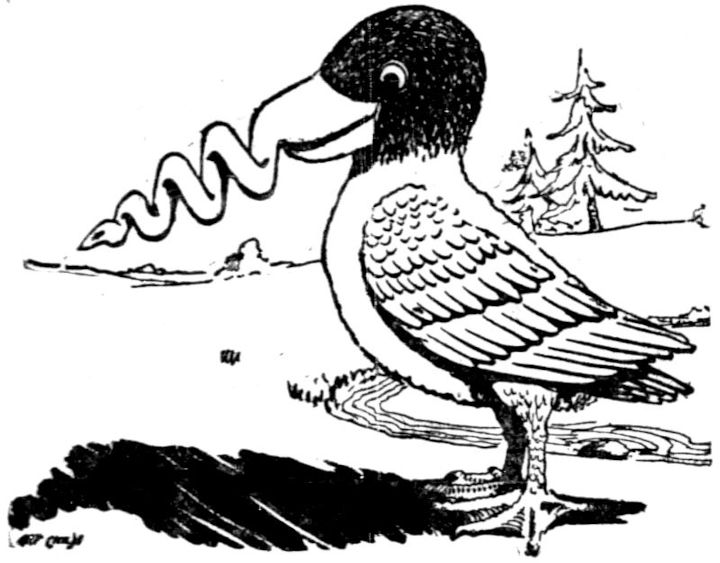

“Hmm,” drawls the guide, pursing his lips, “look’s like a swamp-auger has passed this way. Never heard of a swamp-auger? Well, he’s a great big bird, kind of built on the order of a duck. And he has a bill that’s like a corkscrew. It’s mighty handy, too, because he uses it to get his food with. He Just bores; right down into the swamp for worms, you see. Sure enough, there’s a little hole here. See it? There’s where the swamp-auger was boring.”

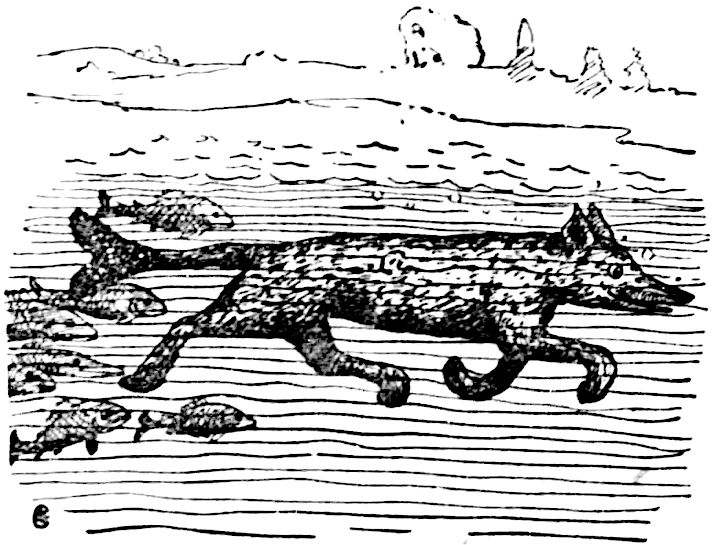

THE FISH-FOX

“Snowshoe Bill had a visitor. He was a younger guide, with tanned skin, keen black eyes, and a flashing smile. The two of them smoked and looked over the ripples that danced in the sun.

“Catching many fish?” asked the visitor.

“Quite a few,” answered Bill. Then he raised his voice loud enough for the nearby tenderfoot to hear. “By the Way, whatever became of that fish-fox your father had when you were a kid.”

“Poor old foxy!” replied the young guide sadly. “He grieved himself to death after dad died. He was a dandy, all right. Why, all father had to say, was ‘Foxy, old fellow, we want fish for supper.’ and away he would go to the lake and dive in. Then he’d make a noise like an angleworm and the fish would follow him right out of the water onto the shore and up to the cabin. All dad had to do was to take a club and kill as many as he wanted and tell Foxy to take the rest back to the lake. Some fish we had then.”

The young fellow took a sidelong glance at the open-mouthed listener. Then winked at Snowshoe Bill and said lazily, “Ho, hum. Those were the happy days.”

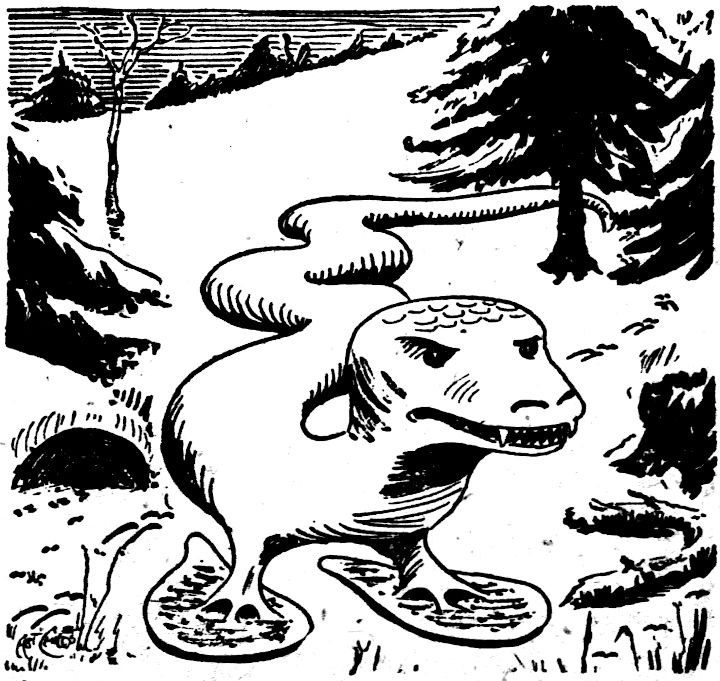

THE SNOW SNAKE

“’Fraid of snakes, did you say, sister?” asked the old guide as he smiled at Paula, whose father had brought her up to his favorite place in the North Woods for an early season weekend camping trip.

”I should say I am!” answered Paula. “I’d run miles and miles if I caught the tiniest sight of one!”

“Then I guess you’d be running yet if you’d seen the snow snake I saw last Winter,“ chuckled the old guide. “Lucky you weren’t here then.”

“What’s a snow snake?” demanded Paula.

“Well, miss, I’m one of the few that can answer that question, and it was rare luck for me to catch sight of this fellow, because they rarely get so far south as this. About the farthest south they get in Winter is the timberlands along the Canadian border. Right now I reckon the snow snakes are away up around Hudson Bay.”

“I’d heard first of these snakes from the Indians, who have lots of legends about them. They are supposed to live on owls, weasels and other birds and animals that prey on rabbits, grouse and other favorite game up here. So, you see, the snow snake is a pretty good fellow.”

“Farther up north when you see winding trails in the snow the Indians always tell you the snow snake makes them, and I guess they know.”

THE OOMPH

Down by the old logging road Mrs. Partridge was sitting on her nest. At the approach of danger she scuttled off the nest and hid in the underbrush. The intruders counted fourteen pretty eggs.

“There’s a raspberry patch a little further down,” remarked the guide, “and I think there’s another nest near it. Want to take a look?”

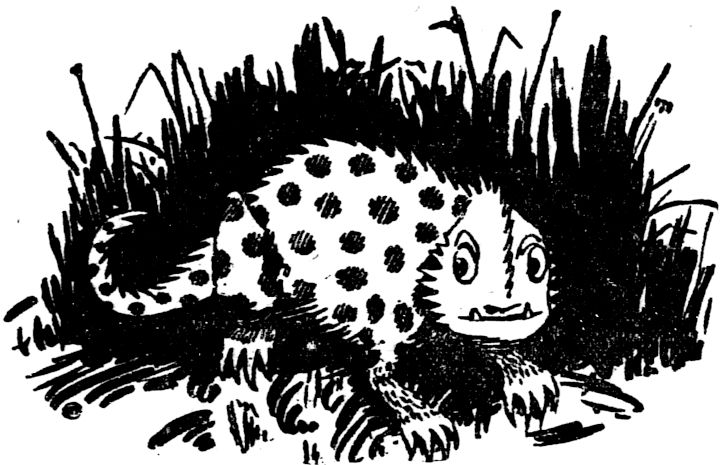

The tenderfoot followed him eagerly. There was the nest, sure enough, but all the eggs were gone—only a few shells left. The guide shook his head sadly. “It’s the oomph’s work,” he explained. “He’s a hard-looking animal, the worst enemy the birds have in nesting season. There’s a big bounty on the oomph, but he’s sly and hard to get.”

“In case you see an animal about as big as a dog, but looking like a cross between a big lizard and a toad with long claws and with sharp spines all along his back and big spots all over him, get him quick. He’s an oomph. He goes around hunting birds’ nests, and when he finds one he makes a noise deep down in his throat that sounds like ‘oomph, oomph.’ That’s how the old boy gets his name.”