The Washington Times, January 25, 1920

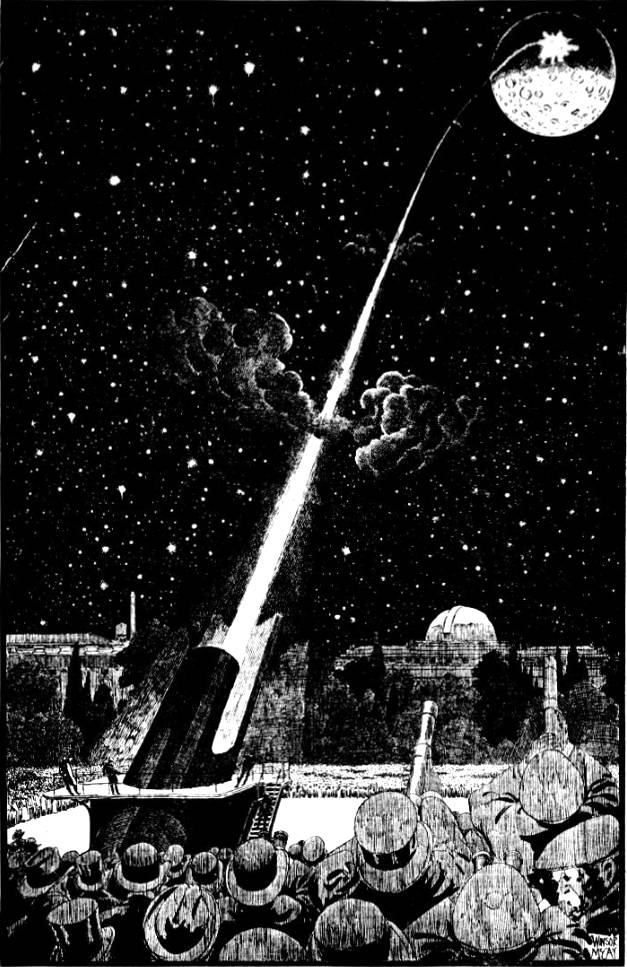

If you pointed your cannon straight up toward the moon, or aimed at the moon your rocket, as Professor Goddard is preparing to do, you would hit the moon if your projectile left the earth at a speed equal to six and seventy-seven-hundreths miles per second. This rate of speed would take the projectile up through the earth’s little air cushion, about two hundred and thirty miles thick, and on beyond to a point in space where the earth’s power of gravitation would end and the moon’s power would begin. The projectile would shoot up the first part of the journey, “fall down” the second part, landing on the moon inevitably. The plan is to charge part of Professor Goddard s rocket with some brilliantly inflammable and explosive stuff, aim it at a dark moon, then watch with telescope and see by the flash that the messenger had struck the moon’s surface and exploded.

This is not a Jules Verne theory, but the deliberate planning of scientific men.

If men could reach the moon they would be surprised at their own power. Because gravity’s power is so light on the moon and because of freedom from atmospheric pressure, an earth man on the moon could run faster than a swallow could fly, throw stones over mountains and jump from precipices without being hurt.

On the moon, for instance, you have fifteen days summer, while the sun is visible, then fifteen days of most terrific winter, during the nights, when there is no heat, and so it goes all through time, winter and summer, night and day, every fifteen days.

The sun gives about three hundred thousand times as much light as the moon gives. The moon sends us some heat, but it would take millions of moons to supply enough heat to make the earth habitable if the sun’s heat should fail us.