Evening Star, Washington D.C., October 18, 1908

FLYING DRAGON AND REPTILES

By James Carter Beard

IT was not many years ago, at a time when winged dragons were ranked with centaurs, hippogriffs, unicorns, and mermaids as impossible monsters, to be looked for only fairy tales and heraldic devices, that to everyone’s fossil remains of these same winged dragons were actually discovered in limestone in the vicinity of the village of Solnhofen, Bavaria. Speaking of these fossils, Charles Kingsley facetiously remarked. “People them pterodactyls, only because they are ashamed to call them flying dragons after denying so long that flying could exist.

IT was not many years ago, at a time when winged dragons were ranked with centaurs, hippogriffs, unicorns, and mermaids as impossible monsters, to be looked for only fairy tales and heraldic devices, that to everyone’s fossil remains of these same winged dragons were actually discovered in limestone in the vicinity of the village of Solnhofen, Bavaria. Speaking of these fossils, Charles Kingsley facetiously remarked. “People them pterodactyls, only because they are ashamed to call them flying dragons after denying so long that flying could exist.

But folks, and especially scientific folks, before these fossils were found, were not entirely without excuse for doubting the existence of such creatures. The only fact is that the only animals now living, barring insects, that can really fly are birds and bats. Many animals said to fly, as, for instance, flying squirrels, do not really fly; but are capable of sailing down from a higher to a lower position in a more or less slanting direction, only by the aid of a flap of skin extending along the flanks from the fore legs to the hind ones, which, when the limbs are spread apart as far as possible, makes a sort of parachute like extension from the body, preventing an abrupt descent to the ground Neither do flying fish really fly; but, impelled by a vigorous rush through the water, spring, wet and glittering, from a wave, and. upborne on their large, flat breast wings, which serve them as aeroplanes, are carried in a straight course through the air as long as the impetus lasts or their wings remain wet, after which they drop incontinently back into their native element They sometimes travel for two hundred yards at the rate of fifteen miles an hour, rising twenty-five feet above the water It is magnificent; but it is not flying There are several species of lizards too that take short swoops through the air, supported by an expansion of the skin stretched on several much elongated ribs, so as to form a sort of half-kite on each side of their bodies. One species called the flying gecko is furnished with a broad flap or rim which extends around body, tail, and limbs But the most singular of these so called flyers is the flying treetoad, which, by means of membranes extending between its fingers and toes, is enabled as it leaps to descend more easily from branch to branch.

The Real Flyer

THE real flyers, in fact, belong to only two out of the six great classes into which naturalists have divided all animals possessing backbones, — the birds, and the bats. There is not a hint among all the different species of reptiles now living of the possibility of wing development: so our forebears in their realm of science, upon the evidence then before them, could not well do otherwise than disbelieve in the possibility of flying reptiles To the science of their day, flying reptiles were unthinkable.

But, like many other things that have been unthinkable to men of science, such, for instance, as the existence of marine animals at enormous depths in the ocean, the actual existence of which has been demonstrated by catching and dragging them through miles of water to the surface, the fact that flying reptiles really lived on the earth at one time in the world’s history can no longer be disputed by those who possess even a limited acquaintance with science.

Used by the First Artist

NORTH of the Danube River in Bavaria is found a whitish yellow limestone “Lithographic stone,” artists call it and employ it to make their pictures on: but Nature, the first of all artists, used it long before for this same purpose. It now forms a series of low, flat topped hills, separated from one another where parts of the formation have been gradually worn away by ice and water. Geologists call this the white jura limestone of Germany, and assure us that as calcareous mud it once formed the bottom of a sea that existed only in remote times

In the inconceivably remote period to which reference is here made, many objects that had fallen into its waters and sunk to the bottom were buried in fresh accumulations of this mud. deposited by currents from inland streams which emptied into it, — multitudes of shells, of course, fish, large and small, sea urchins, king crabs, and even the forms of the quickly dissolving jellyfish, together with fragments of land plants, dragon flies, and other insects, and turtles and lizards, even birds still covered with their feathers,– birds of which no human being ever saw a living specimen,– and last, though by no means the least, remains of the wonderful pterodactyls.

Sometimes the rock in which they lie embedded splits up into thin layers like the leaves of a book, — a great ancient book of stone, written, illustrated. and bound by no human agency, amid the pages of which are to be found revelations a of an antiquity compared with which the oldest records of man are as yesterday.

It was in this book of Nature that a director of the Palentine Museum at Mannheim beheld the first fossilized remains of a pterodactyl ever seen by man. He thought that it was the skeleton of a marine animal Cuvier. the great naturalist, obtained the specimen afterward, and saw at once that it was the skeleton of a creature entirely new to science, one that had never entered into the mind of man to imagine. He called it a pterodactyl from the Greek pteron (wing) dactylos (finger), because, unlike any other creature of which he had had any previous knowledge, the animal evidently when alive had possessed wings consisting of an expansion of the skin from the body to the little finger of each of its hands the digits being enlarged and lengthened to an immense extent to support the wings, as the gaff supports the upper edge a fore and aft sail.

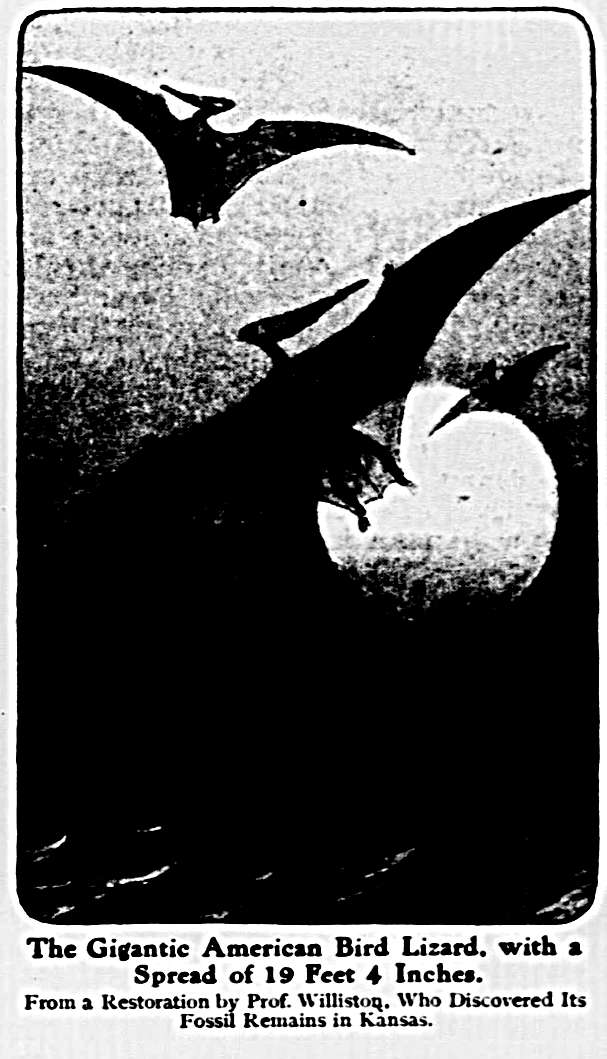

Since the time of Cuvier large numbers of these bird lizards have been described from fossils found principally in Europe and America, varying in size from those smaller than a sparrow to enormous creatures, with a spread of wing measuring from eighteen to twenty feet.

Writing of these larger species, the late Sir Richard Owen said, “The flying reptile on outstretched pinions must have appeared like the soaring roc of Arabian romance; but with the features of leather wings and crooked claws superinduced, and gaping mouth with threatening teeth.”

Appearance of the Monsters

THE structure and appearance of the creatures varied as greatly as their dimensions. In some the head is prodigiously lengthened, in others it is shorter and thicker, and in others again moderate in size. The neck, whether stout or slender, is generally long, and while some have only the mere vestige of a tail, others rejoice in one — with a sort of flat paddle at the end — almost as long as the head, neck, and back of the animal combined. But whatever their size or proportions, pterodactyls were without doubt the weirdest, most impossible looking, nightmarish creatures that ever existed on this earth: all the more so because, unlike the grotesques born of artistic imagination, they were not made up of a heterogeneous assortment of odds and ends of other creatures: but had a conformity of parts all their own, and, so to speak, an originality of structure that cannot really be identified with any class of vertebrate animals now living.

Were they flying reptiles? They are called so; but a number of paleontologists believe them to have been more nearly allied to birds. They had brains like those of a bird, and beaks,–hollow bones with apertures in them to be filled with air. Like a bird, they were warm blooded and had wings; but they had not a single feather with which to clothe their naked skins; and they had four legs. That they were not mammals was evident to the investigators

Did they lay eggs as do birds and most of the reptiles? If so, why is none ever found? Did they build nests? What did their young resemble? They must have had young; but no remains of such have ever been found. Why? Were these naked birds plain or brilliantly colored as are the skins of the so called flying lizards of to-day? Had pterodactyls voices? How came they to exist, and. seemingly without any intermediate forms, become at once adapted for flight? And finally, how came the whole race to perish?

Problem for Future Scientist

IS it possible for the reader to conjecture that in the far future, as far removed in point of time from our day and generation as is the geological age in which pterodactyls flourished. some inconceivably endowed creatures may chance upon fossil remains of the genus homo? If so, one may conjecture how impossible it is to imagine what will be the ideas of such future intelligence with respect to their find, or the questions that may arise concerning the nature of the nondescript creatures whose remains they will have discovered. Whatever the questions are that will so arise, it is certain the dead bones will not be able to answer them all, as it is that the science of to-day is unable to answer one out of scores of questions that occur regarding pterodactyls.