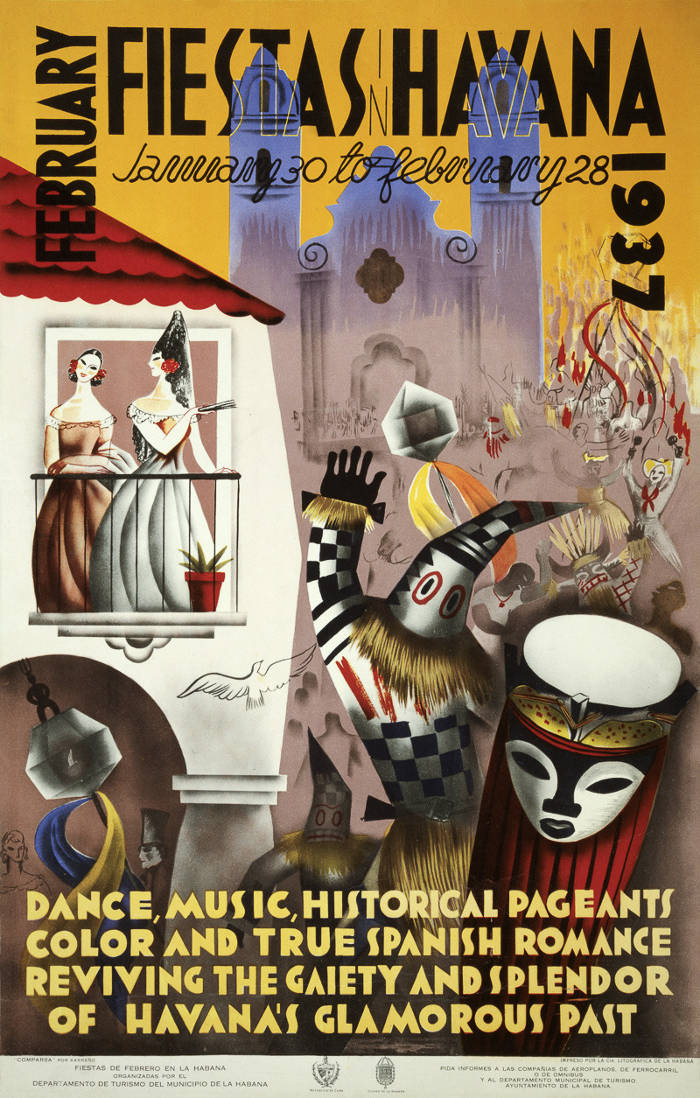

Travel Poster for Havana Cuba, 1937

Month: April 2019

Dr. Livingstone, I presume?

A couple of maps showing the routes of Scottish Missionary, David Livingston, as he searched for the source of the Nile river. Because of his explorations he was a popular hero in the late 19th century, and because of his fame, he was influential in ending the East African Arab-Swahili slave trade.

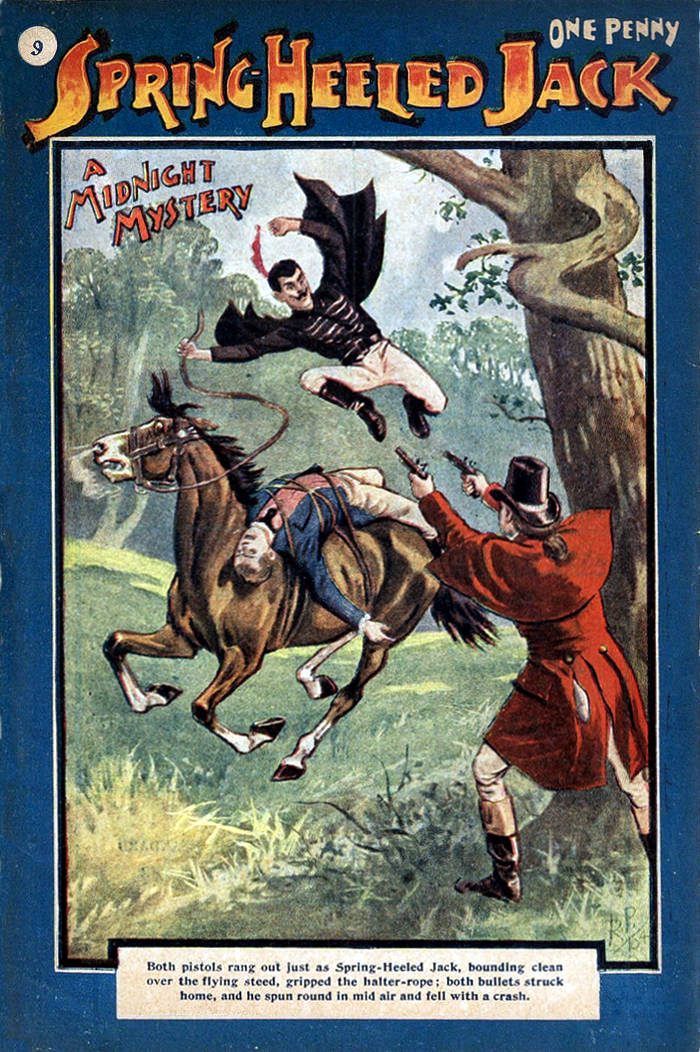

A Midnight Mystery

Both pistols rang out just as Spring-heeled Jack, bounding clean over the flying steed, gripped the halter-rope; both bullets struck home, and he spun round in mid air and fell with a crash.

Spring-Heeled Jack, 1904, issue #9

Thought Earth Hollow, 1923

Godzilla Storyboard, 1954

Storyboard images from the 1954 movie Godzilla.

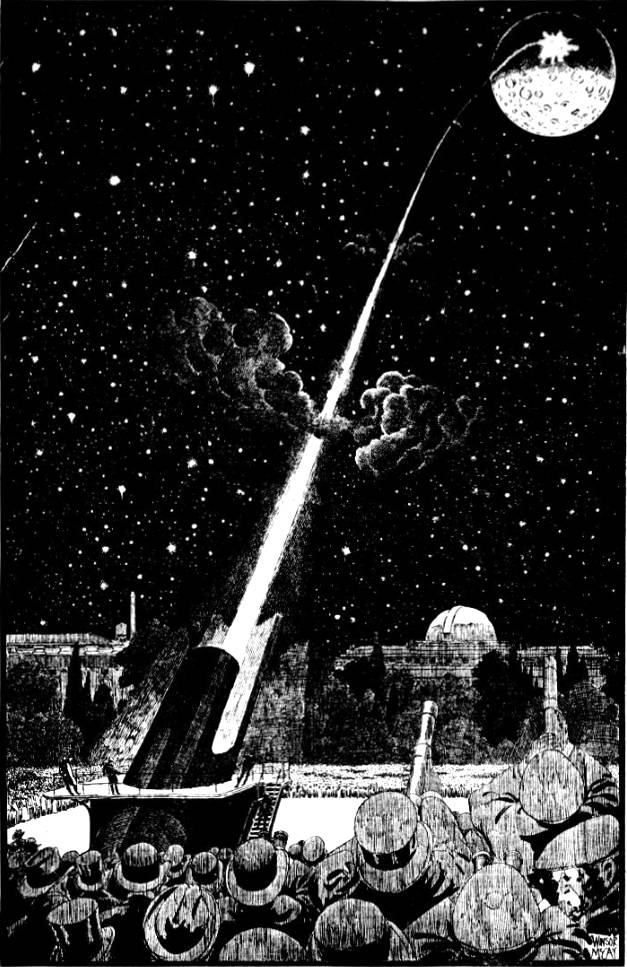

Shoot the Moon, 1920

The Washington Times, January 25, 1920

If you pointed your cannon straight up toward the moon, or aimed at the moon your rocket, as Professor Goddard is preparing to do, you would hit the moon if your projectile left the earth at a speed equal to six and seventy-seven-hundreths miles per second. This rate of speed would take the projectile up through the earth’s little air cushion, about two hundred and thirty miles thick, and on beyond to a point in space where the earth’s power of gravitation would end and the moon’s power would begin. The projectile would shoot up the first part of the journey, “fall down” the second part, landing on the moon inevitably. The plan is to charge part of Professor Goddard s rocket with some brilliantly inflammable and explosive stuff, aim it at a dark moon, then watch with telescope and see by the flash that the messenger had struck the moon’s surface and exploded. Continue reading “Shoot the Moon, 1920”

Question Posed by Vanity Fair, May, 1922

Skull Rock, 1897

West Superior, Wis.. July 20.—On a steep, rocky bluff overhanging a narrow inlet of the Lake of the Woods, about two and one half miles from the mining village of Rat Portage, Ontario, stands one of the most freakish objects to be found anywhere in the world. It consists of a ledge of solid granite which bears a most grotesque resemblance to a human head, its cavernous mouth partly open, its features distorted with a horrible grin. Rude art has supplemented nature in perfecting the resemblance. This monstrosity is commonly known as “Devil’s head,” but is also called “skull rock.” It is about twenty feet high above the bluff, and about twenty-one feet in width at the widest part. Ears, eyes, and a mouth are plainly visible —the latter appearing in the form of a cave, which extends back in the stone about ten feet, and then, like a veritable throat, shoots down a considerable distance into the hill on which it rests. Continue reading “Skull Rock, 1897”

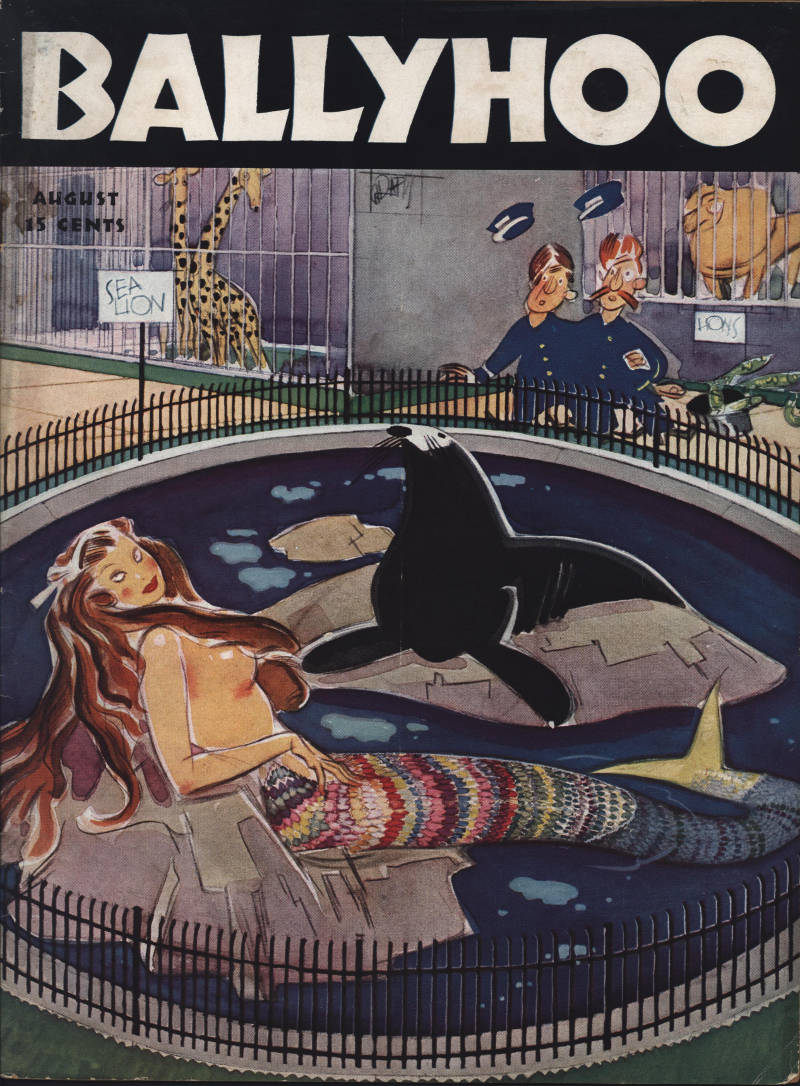

Ballyhoo, Aug, 1936

Flying Dragon and Reptiles

Evening Star, Washington D.C., October 18, 1908

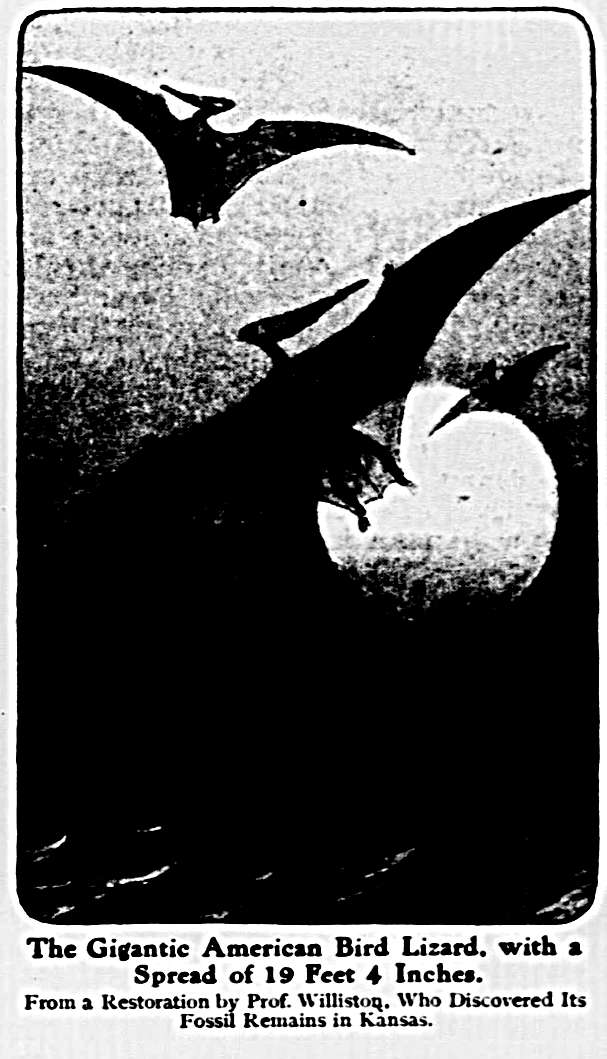

FLYING DRAGON AND REPTILES

By James Carter Beard

IT was not many years ago, at a time when winged dragons were ranked with centaurs, hippogriffs, unicorns, and mermaids as impossible monsters, to be looked for only fairy tales and heraldic devices, that to everyone’s fossil remains of these same winged dragons were actually discovered in limestone in the vicinity of the village of Solnhofen, Bavaria. Speaking of these fossils, Charles Kingsley facetiously remarked. “People them pterodactyls, only because they are ashamed to call them flying dragons after denying so long that flying could exist.

IT was not many years ago, at a time when winged dragons were ranked with centaurs, hippogriffs, unicorns, and mermaids as impossible monsters, to be looked for only fairy tales and heraldic devices, that to everyone’s fossil remains of these same winged dragons were actually discovered in limestone in the vicinity of the village of Solnhofen, Bavaria. Speaking of these fossils, Charles Kingsley facetiously remarked. “People them pterodactyls, only because they are ashamed to call them flying dragons after denying so long that flying could exist.

But folks, and especially scientific folks, before these fossils were found, were not entirely without excuse for doubting the existence of such creatures. The only fact is that the only animals now living, barring insects, that can really fly are birds and bats. Many animals said to fly, as, for instance, flying squirrels, do not really fly; but are capable of sailing down from a higher to a lower position in a more or less slanting direction, only by the aid of a flap of skin extending along the flanks from the fore legs to the hind ones, which, when the limbs are spread apart as far as possible, makes a sort of parachute like extension from the body, preventing an abrupt descent to the ground Neither do flying fish really fly; but, impelled by a vigorous rush through the water, spring, wet and glittering, from a wave, and. upborne on their large, flat breast wings, which serve them as aeroplanes, are carried in a straight course through the air as long as the impetus lasts or their wings remain wet, after which they drop incontinently back into their native element They sometimes travel for two hundred yards at the rate of fifteen miles an hour, rising twenty-five feet above the water It is magnificent; but it is not flying There are several species of lizards too that take short swoops through the air, supported by an expansion of the skin stretched on several much elongated ribs, so as to form a sort of half-kite on each side of their bodies. One species called the flying gecko is furnished with a broad flap or rim which extends around body, tail, and limbs But the most singular of these so called flyers is the flying treetoad, which, by means of membranes extending between its fingers and toes, is enabled as it leaps to descend more easily from branch to branch. Continue reading “Flying Dragon and Reptiles”