Gigantic Planets, the Captives of Strange Suns, Whose Nightmarish Creatures

Live In Air Thicker Than the Ocean Depths Where the Titanic Lies

By Professor Garrett P. Serviss, the Distinguished Astronomer.

Copyright, 1912, by American-Examiner. Great Britain Right Reserved.

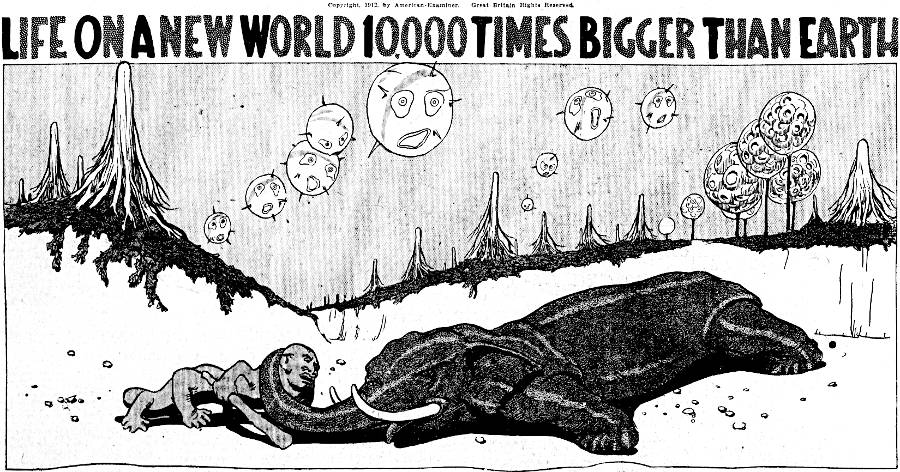

“Imagine the scene on this enormous world. If we thing of its inhabitants in our own familiar forms we would see grotesque, crawling creatures like the elephant, flattened to the planet’s surface by the enormous pull of gravitation. man would be a weird caterpillar, trees would grow with their branches dragged to the earth or develop balloon-like foliage and the birds would be humble globes of life floating through the thick air.”

“Imagine the scene on this enormous world. If we thing of its inhabitants in our own familiar forms we would see grotesque, crawling creatures like the elephant, flattened to the planet’s surface by the enormous pull of gravitation. man would be a weird caterpillar, trees would grow with their branches dragged to the earth or develop balloon-like foliage and the birds would be humble globes of life floating through the thick air.”

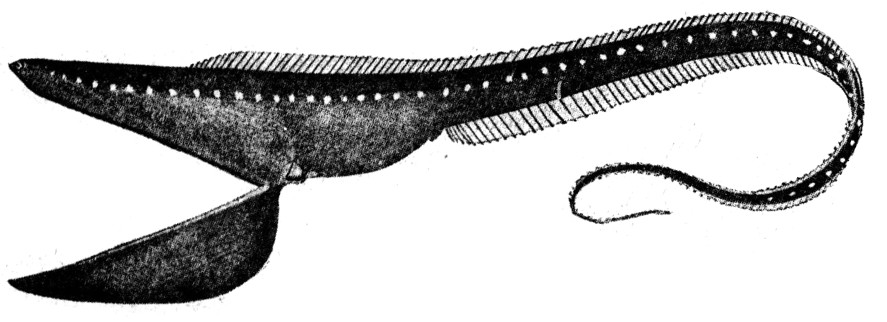

One of the grotesque, flattened, deep sea fish, Built to live in water no denser than the air on the great planet.

One of the grotesque, flattened, deep sea fish, Built to live in water no denser than the air on the great planet.

“Or it may be that the inhabitants are nebulous giants to whom a flock of our aeroplanes would be no more than a flock of wasps”

“Or it may be that the inhabitants are nebulous giants to whom a flock of our aeroplanes would be no more than a flock of wasps”

ONE of the most Interesting recent discoveries of modern astronomy is that of the existence of huge Invisible companions to many stars, and still more Interesting is the conclusion that these extraordinary ‘ bodies may be gigantic planets revolving in the light of the stars with which they are connected. If they are planets, they so enormously exceed those that revolve around our sun, in magnitude, that they must be regarded as an entirely different. species of worlds than ours. The earth placed beside one of them, would be like a mouse be side an elephant, or a trout beside a whale.

Even the great planet Jupiter, which is 1,300 times as large as the whole earth, would be utterly insignificant in comparison with one of these mysterious bodies which has been found revolving around the star Algol in the northern sky. That body is more than a million times as large as the earth. In fact, it is almost as large m the star around “which it revolves although that star is larger than our sun and yet it is utterly invisible, except at certain periods when it passes between us and Algol and thus causes a partial eclipse of its bright companion. Even then it cannot be seen directly, and its form and dimensions are estimated from the amount of obscuration that it causes. Its diameter is calculated at about 840,000 miles.

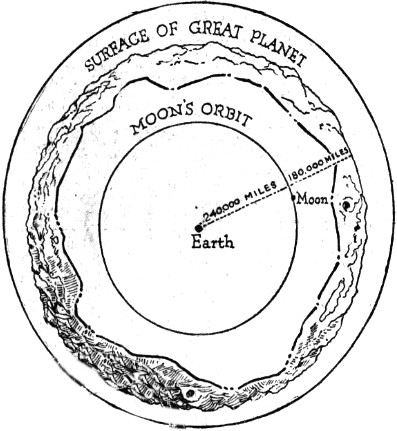

We can get a realizing sense of what this means if we imagine that tremendous world to be a hollow sphere, with the earth placed at its center. Then there would not only be plenty of room for the moon to continue to revolve round the earth, as it now does, at a distance of 240,000 miles, but there would be a clear space of 780,000 miles on all sides between the orbit of the moon and ,the inside of the shell of the Brodignagian planet!

We can get a realizing sense of what this means if we imagine that tremendous world to be a hollow sphere, with the earth placed at its center. Then there would not only be plenty of room for the moon to continue to revolve round the earth, as it now does, at a distance of 240,000 miles, but there would be a clear space of 780,000 miles on all sides between the orbit of the moon and ,the inside of the shell of the Brodignagian planet!

The surface of such a planet exceeds that of the earth ten thousand times. The Atlantic ocean stretched out upon it, to the same relative sirs that it is on the earth, would be more than 300,000 miles broad. If it had surface features exactly proportioned to those of the earth, its loftiest mountains would be from 400 to 500 miles high, and its oceans from 200 to 600 miles deep! A distance corresponding to that between New York and Chicago would be ninety thousand miles long. And, if everything were constructed on the same scale, men would be 600 feet tall, and the giant redwoods of California eight or nine miles high!

Of course, the force of gravity, or the weight of bodies, must also be enormously increased. If we suppose the mean density of the giant planet to be the same as that of the earth, a body that weighs one pound here weighs about a hundred pounds there, and an average man, having the same size that be has on the earth, would there weigh seven and a half tons. But if he were 600 feet tall that is to say, proportioned to the size of the planet he would weigh seven and a half million tons.

But there are many other interesting calculations, all based upon perfectly well known principles, that can be made about the condition of things on a world so gigantic as that which accompanies Algol. We may, for instance, inquire about the state of its atmosphere. The density and nature of the air surrounding any planet, depend upon the force of gravity of that planet. If the planet is very small, the force with which it holds bodies, or gases, upon its surface is proportionately small. Thus we know that a little world, like the moon, on which the weight of bodies is only about one-sixth as great as on the earth, is unable to hold permanently under its control any of the light gases which constitute the air that we breathe. The lighter a gas the quicker it escapes, because its molecules are in more rapid vibration than those of heavier gases. A gas is a substance in which the molecules are continually flying about in every direction, with a speed depending upon the nature of the gas, and unless the attractive force of a planet is sufficient to restrain the molecules of a gas when their direction of flight, happens to be away from the center of the planet, then those molecules, and ultimately the whole of the gas, will escape into outer space.

To determine whether any planet is able to hold the gases that make an atmosphere, we find out, from its size and density, what speed a gaseous molecule, or any other particle of matter, would have to have in order to fly directly away from it and never return. In the case of the earth this speed is known to be about seven miles per second. If, then, any particle should start away, radially, from the surface of the earth’s atmosphere, with a velocity ‘ exceeding seven miles per second, it would escape into space and never come back. Now, the molecules of hydrogen have a maximum velocity of vibration exceeding this limit, and, as a consequence, we find no free hydrogen in the air. But the molecules of oxygen and nitrogen, and the other gases which are found in air, have velocities less than seven miles per second, where fore they remain attached to the earth and form an invisible atmosphere around it.

On the other hand, a very great planet, like that of Algol, would retain not only the constituents of our air, but also the volatile hydrogen which escapes from the earth’s control, and, for all that we know, other gases — if there be any whose molecular velocity is greater than that of hydrogen. Thus we see that the atmosphere of so huge a planet must be widely different In its composition from the air to which we are accustomed.

What the consequences of the existence in the atmosphere of a planet of free hydrogen might be it is difficult to guess. We know that hydrogen when mixed in certain proportions with oxygen will explode with extreme violence at the touch of a flame or an electric spark. Suppose a planet, like that of Algol, to be surrounded with an atmosphere, containing hydrogen mixed with oxygen, and suppose that, owing to some cause, the mixture attains, at some point, the explosive ratio — and then let a flash of lightning pass through it! It is conceivable that the resulting explosion might have the most dreadful consequence. It is worth while considering whether this may not be the real cause of some of the sudden outbursts of what are called “new stars.”

Then, too, upon such a planet the density of the atmosphere would be far greater than upon earth. Here the air presses with a force of fifteen pounds to the square inch; on the companion of Algol — making the same supposition as before regarding the planet’s density the pressure would amount to three quarters of a ton per square inch!

Now, if it could be. supposed , that the inhabitants of that planet were composed of substances of relatively small density, so that an animal as large as a man would weigh no more there than a man does here, they would almost be able to float in the air, and with comparatively slight, aid could actually do so, Aerial navigation would , be as easy and natural to them as swimming is to us.

This leads us to another consideration. We have thus far assumed that the mean density of the great planet in the Algol system is equal to that of the earth. The probability, is, however, that, its density may not be more than one-quarter of the earth’s. This calculation is based both upon observation and upon analogy. The mean density of the sun, which is a body of nearly the same size as that with which we are dealing, is one quarter of the earth’s density. In that case the, total gravitation of the planet would be only 250,000 times greater than the earth’s, and the weight of bodies on its surface would be reduced to twenty-five times their weight here. But even then the pressure of its atmosphere, supposed to be relatively of the same extent as the earth’s atmosphere, would be 375 pounds to the square inch which is a much higher pressure than any careful engineer would dare to put into the best steam boiler. A cubic yard of that air, removed to the earth’s surface and allowed suddenly to expand, would blow a building to pieces like an explosion of dynamite!

But we have not yet touched upon all the curious consequences resulting from the great size of the mysterious planet near Algol. Assuming that its mean density is one quarter that of the earth; and that, consequently bodies upon its surface weigh twenty-five times as much as the same bodies do here, we may reasonably conclude that its inhabitants, instead of being giants proportioned to the great size of their world, must rather be dwarfs, only a foot or two in height. This conclusion results from the consideration that, if they were as large as the inhabitants of the earth they would be unable to stand up under their immense weight. It would crash them down. On such a planet an average man would weigh 3,750 pounds. (This differs from our former estimate of 15,000 pounds,, or 7 1/2 tons, because we now assume that the density of the planet is but a quarter of the earth’s instead of being equal to it).

But could a man of that weight possibly stand upright? Apparently, the only way in which locomotion would be possible to the in habitants of such a world would be by making them so small that their weight would be reduced to a point where bones and muscles could easily support it. This could be accomplished by making the stature of a man about 24 inches. A man of that height on a planet having (at its surface) twenty-five times the gravitative force of the earth would weigh about as much as a six-footer on the earth, and no more. A full-grown elephant, in order to be comfortable, would have to shrink to a height of about four feet or be flattened out like a flounder and move about in that shape.

We have spoken of but one of these great bodies, that which accompanies Algol, but, in fact many others are known. There is a considerable number of stars which have huge dark companions that may be regarded as giant planets. We become aware of their existence by the effects of their attraction upon the stars. It is even possible, in such cases, to calculate the relative size and weight of these invisible bodies. The one near Algol is, as we have said, about 840,000 miles in diameter, while Algol itself has a diameter of about 1,125,000 miles. They revolve round their common center of gravity in the exceedingly brief period of sixty hours, and they are only 3,320,000 miles apart, from center to center.

But this is not all. There is at least one of these giant planetary bodies which is actually larger, or more massive, than its own sun — reversing the ordinary rule with a vengeance. It, is the great body which is connected with the bright star Castor, in the constellation of the Twins.

The arrival of a huge dark body, or stranger planet, in our system, whether it resulted in a collision with the sun or not, would inevitably upset the present planetary system.

The earth and the other planets would be swirled from their orbits; the existing orderly arrangement would be broken up; if the intruder approached close to the sun the latter would burst out with redoubled energies, shrivelling up, perhaps, the whole retinue of its planets like moths in a flame; and the hitherto peaceful worlds, driving wildly hither and thither, might destroy one another in fiery collisions.

(Omaha Daily Bee, June 09, 1912)